Piece Movement: Diagrams

The Pawn

The Pawn can move 2 spaces in the beginning. Afterwards, if unblocked, it can only move one space.

On the first move, the White pawn moves forward 2 spaces. If a pawn is on the starting square and isn’t blocked, it can move 2 squares forward. However, after after it’s off of its original square (whether it moved 2 squares or 1 square for its first move), it can only move one square forward at a time.

Black moves his pawn forward 2 squares as well, blocking White’s e pawn from advancing any further. White cannot move his e pawn forward because of opposition, so he would be advised to find another move.

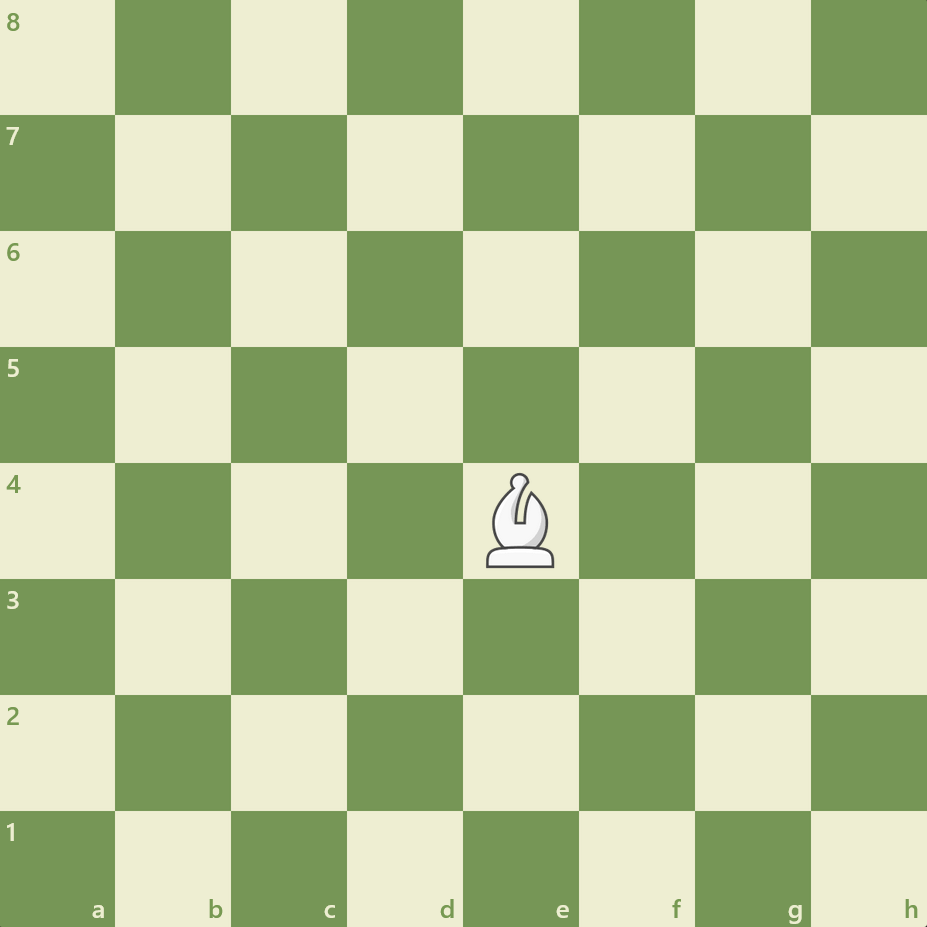

The Bishop

The Bishop can move in diagonals when unblocked by any other pieces. They can zoom from one corner of the board to another! However, bishops cannot move off the color diagonals they start off on.

This is why you’ll hear the terms “dark square bishops,” light square bishops,” and “opposite color bishops,” which are exactly what they sounds like. Dark squared bishops refer to bishops that start on either c1 or f8 (both dark-colored squares), Light square bishops refer to bishops that start on either f1 or c8 (both light-colored squares), and opposite color bishops refer to bishops on, well, an opposite color from one another!

As you can see here, the bishop has massive range. It can move from any square on the b1-h7 diagonal and the h1-a8 diagonal, or 13/64 squares on the board.

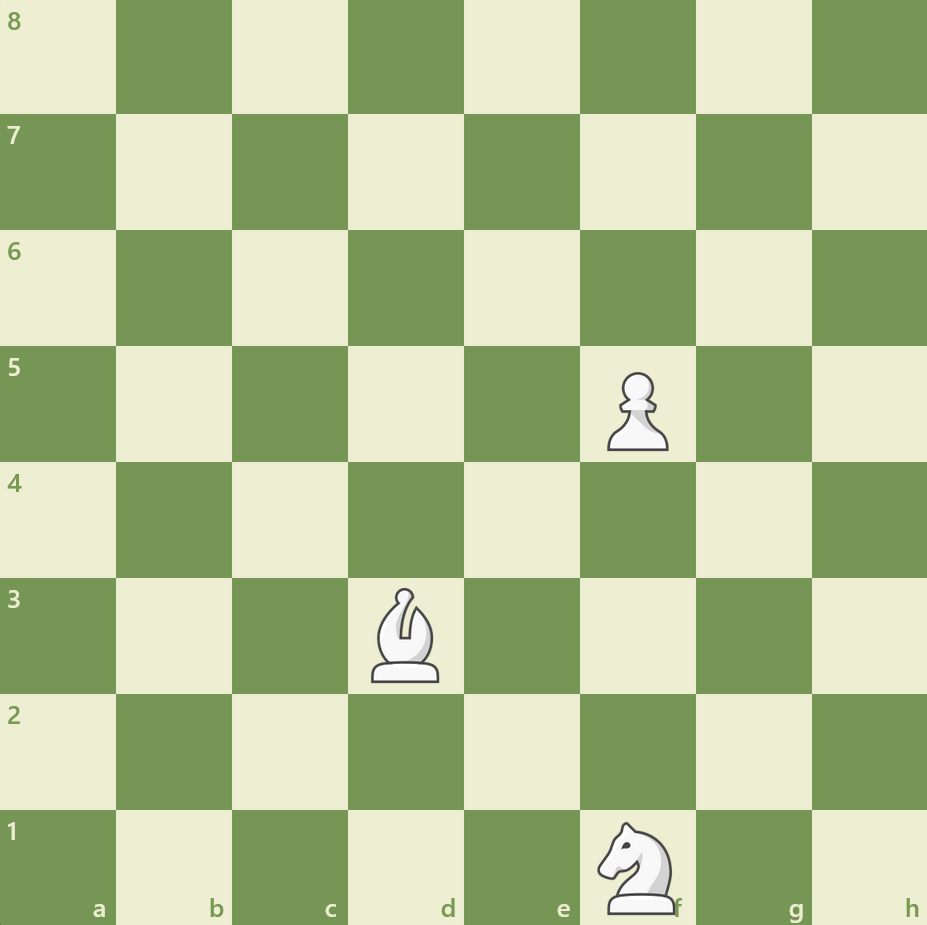

When the bishop is blocked, it has less range. As shown in the diagram, the Bishop cannot move further than e4, because it cannot jump over the pawn or occupy the same square. Similarly, if cannot move to f1 because the Knight is there.

This is why you want to create open diagonals for your bishop, so they can tear through the board!

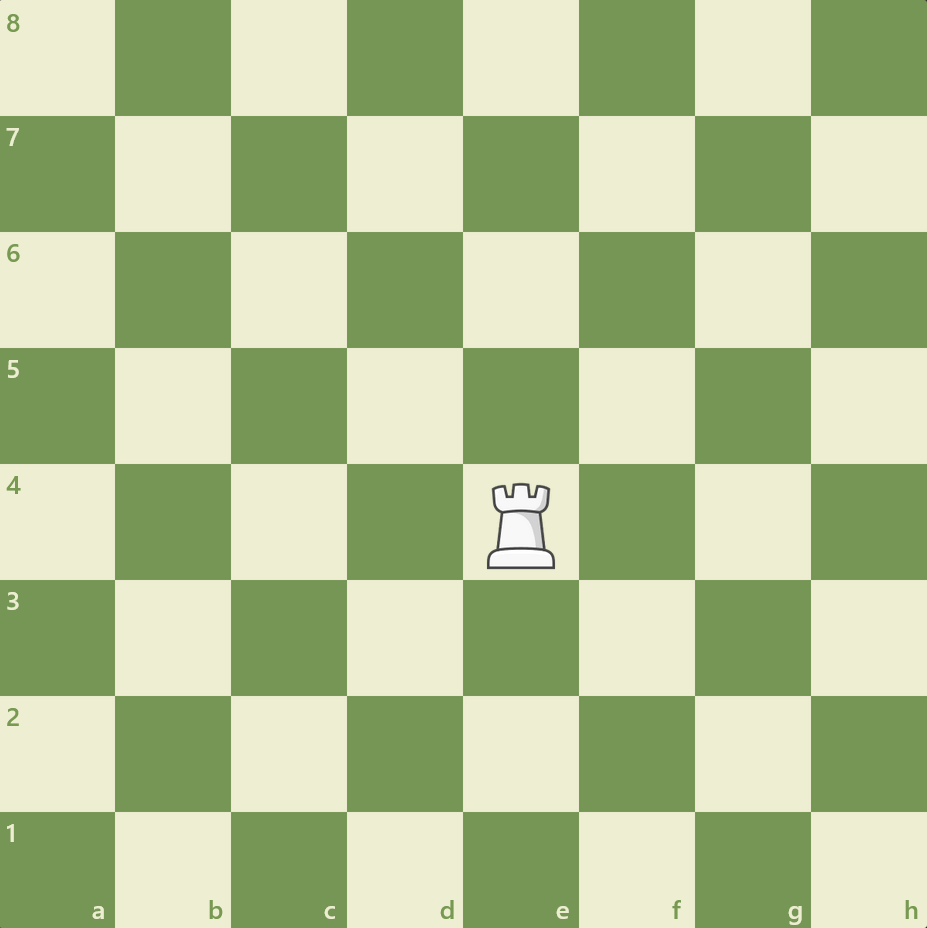

The Rook

As mentioned, Rooks move in horizontal files across the board if unblocked. For instance, the rook in the next diagram can move all the way down the e1-e8 file, and the a4-h8 vertical file. This is why controlling open files with rooks is a good idea.

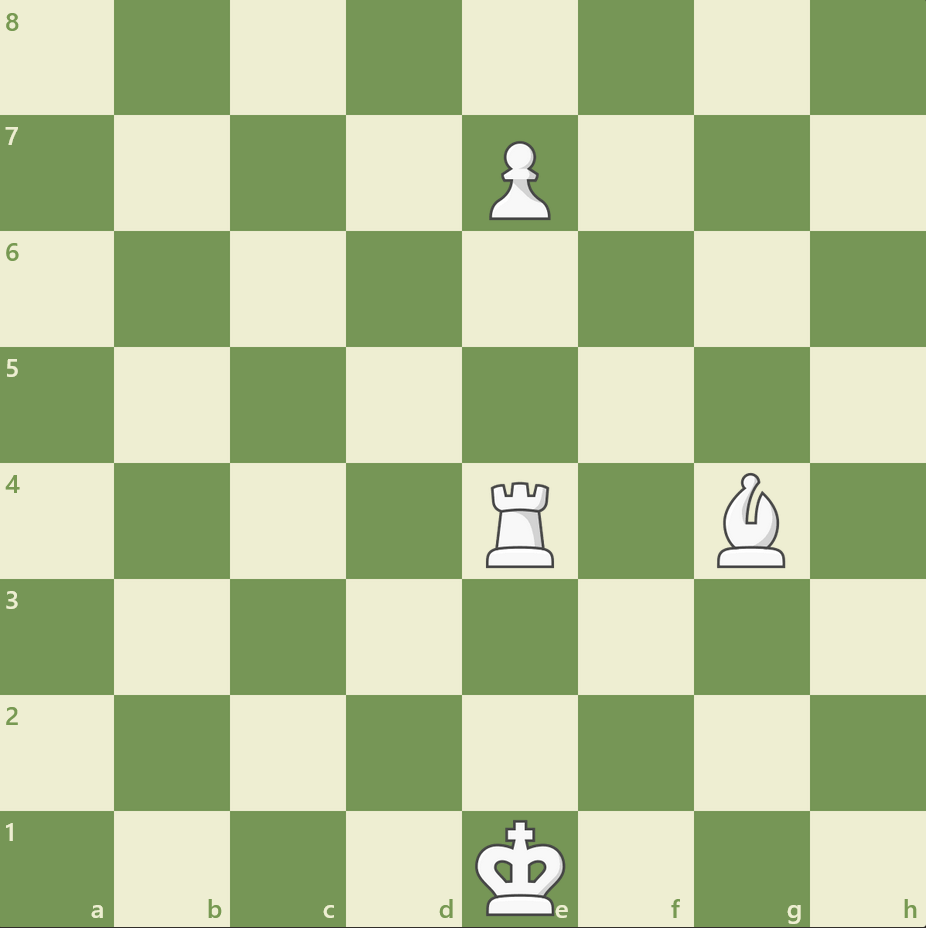

Similar to the bishop, the rook has less range when blocked.

The rook is in the same place as the last example, but it is blocked by both the Bishop, King, and Pawn on three fronts. For example, the Rook is stopped from moving further from f4, e6, and e2 because it cannot jump over other pieces.

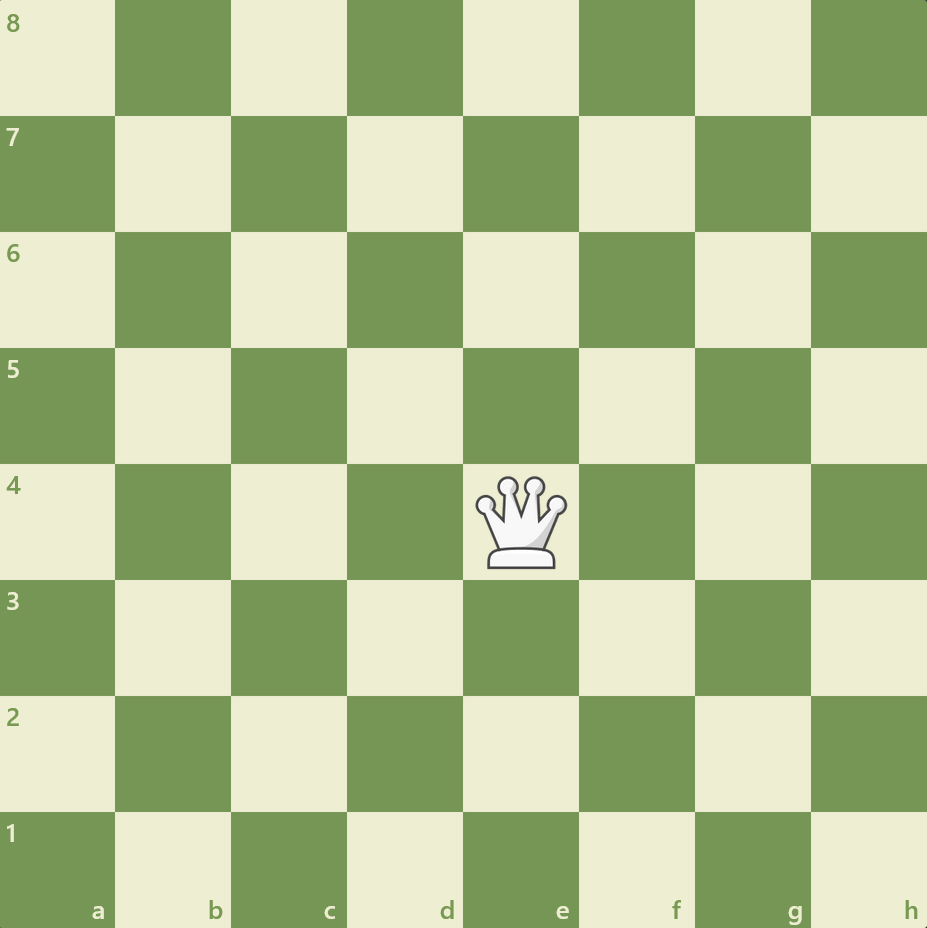

The Queen

The Queen is the most powerful piece on the board for good reason. It can move in both horizontal and diagonal files when unblocked. In the top example, it has full control over the b1-h7 diagonal, a8-h1 diagonal, the e1-e8, a4-h4 diagonals too! Same rules for when it’s blocked applies for the rook, etc, but it’s not hard to see why this is the most powerful piece on the board.

Tip: While it might be tempting to wreak havoc with your queen right away, oftentimes this is not the best choice. As powerful as the Queen is, she is vulnerable to pieces weaker than her (ironically), because normally, you don’t want to lose your Queen to a piece less valuable!

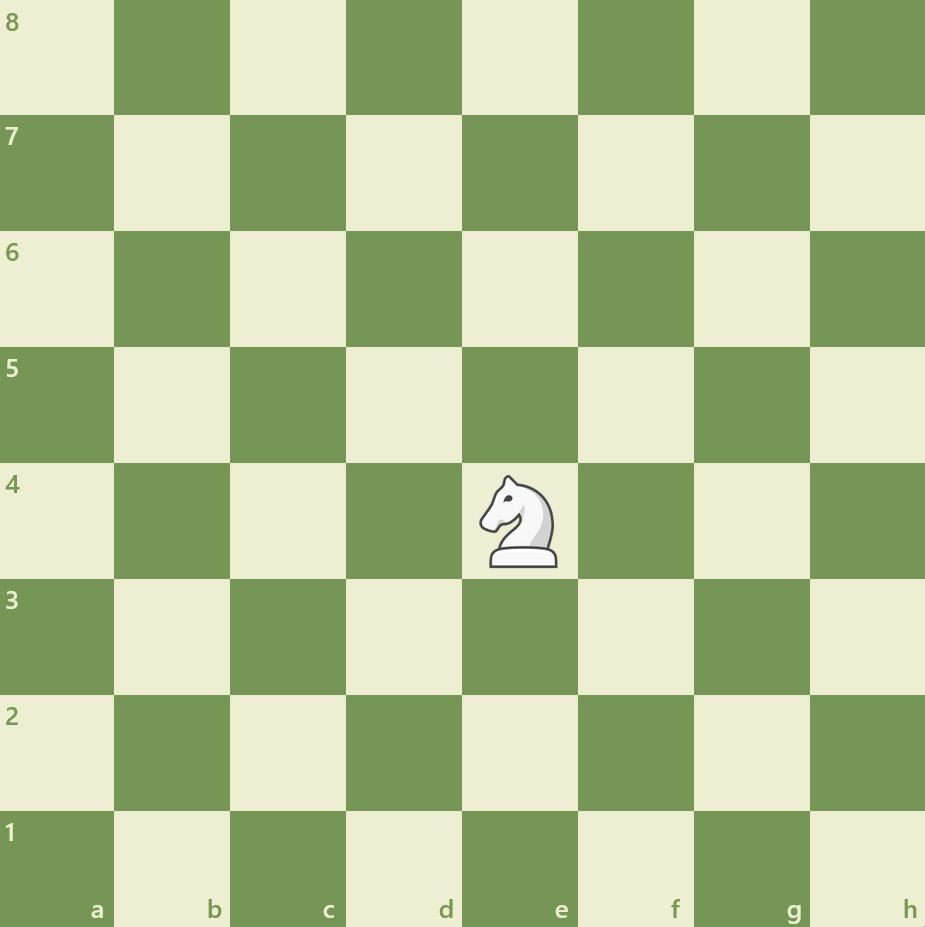

The Knight

The Knight’s movement is the trickiest out of all the pieces. In a nutshell, there are 2 important rules you need to remember.

1) The Knight can jump over other pieces. This is the only piece that can do it.

2) The Knight moves in an “L shape.”

All the over movement rules apply (the Knight can’t move to a square that another piece is occupying, etc), but as you might have guessed already, the knight is very unique and deserves careful scrutiny. Let’s look at some examples now.

As we all know, the letter “L” looks like this:

L

Think of the knight’s movement the same way. It moves in an L. For example, take this position. Where can White move his knight to?

He can move it to f6, f2, g5 g3, d2, d6, c3, and c5. It’s very useful to trace the movement of the Knight out, maybe with a pencil. Notice how when it goes to a square it can move to, it forms a L shape, whether sideways or upright.

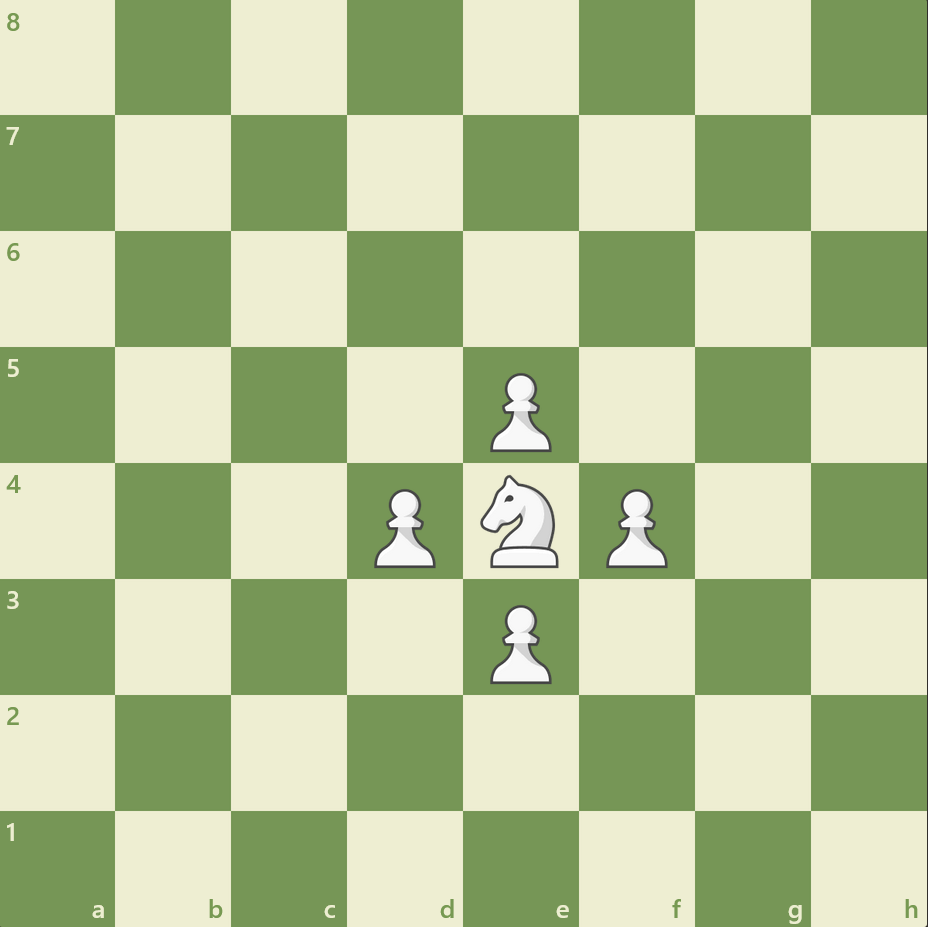

The second rule when regarding Knight movement is that it can also jump over other pieces. Let’s look at an example of this:

The knight seems to be trapped by its own pawns, but it can easily hop out to f6, etc.

The final example is something you might see happen in your own games, and a good illustrator of this concept. Hint, it’s the very first move!

In this position, White has elected to play 1. Nf3 as his first move. See how the knight jumps over the white pawns, and moves in an “L” shape to get to f3.

I recommend you replicate this same movement on your own chess board to get a better feel for how the Knight behaves.

And that’s all there is! Congratulations, you’ve gone through all there is to piece movement. If you’re still not feeling 100% confident on any of these concepts, that’s fine.In order to get more practice, I would highly recommend going to to this link for a visual on how these pieces work. Chess.com does an excellent job explaining, which will make the game much easier. It also covers how a chess game is set up, which is demonstrated below.

Every board is set the same way:

Something very important: As you can see, there are letters and numbers. These indicate where pieces go, and the files. For example, the white Knights are on g1 and b1.

- Pawns start all lined up on the second file.

- Bishops start on the c and squares. For White: c1 and f1. For Black: c8 and f8.

- Knights start on the b and g squares. For White: b1 and g1. For Black: b1 and g1

- Rooks start on the a and h squares. For White: a1 and h1. For Black: a8 and h8.

- Queens start on the d square. For White: d1. For Black: d8.

- Kings start on the e square. For White: e1. For Black: e8.

While this may seem confusing at first, don’t worry! This will make more sense as more information is explained. Now that we’ve got some of the essentials down (albeit a very basic understanding- we’ll cover more in-depth later. Now, let’s move on to two of the most important concepts in chess: Piece Values, Piece Movement, and Capturing/Captures.