Tricky Chess Rules: Pawn Promotion and En Passant

This is the most advanced section of the Beginners Page. We will be delving into these advanced concepts in depth, so don’t worry! You will understand these concepts with enough practice.

I believe the two concepts that we’ll cover in this section — Pawn Promotion and En Passant– are arguably the hardest chess rules that a chess amateur can learn. So, after you master these, you’re a pro!

We’ll be first looking at Pawn Promotion, the easier of the two concepts to understand.

Remember when you covered Piece values? Well, this is where pawn promotion comes in again. In the section for Pawns, I stated that:

“The Pawns are considered to be worth 1 point, but if they manage to promote, they can turn into any other piece (apart from the King), thus changing their value!”

Now, I never mentioned exactly how to promote, so that’s what we’ll be covering right now.

Pawn promotion refers to when one of your pawns reaches the opposite rank at the end of the board, and is allowed to promote to any piece apart from the King. For White, the opposite rank would be the 8th rank, and for Black the opposite rank would be the 1st rank.

Tip: More often than not, you should promote to a Queen. There are only very few instances where another piece is superior, so promote to a Queen!

Promotion is the reward for the lowly foot soldiers near the end of the game.

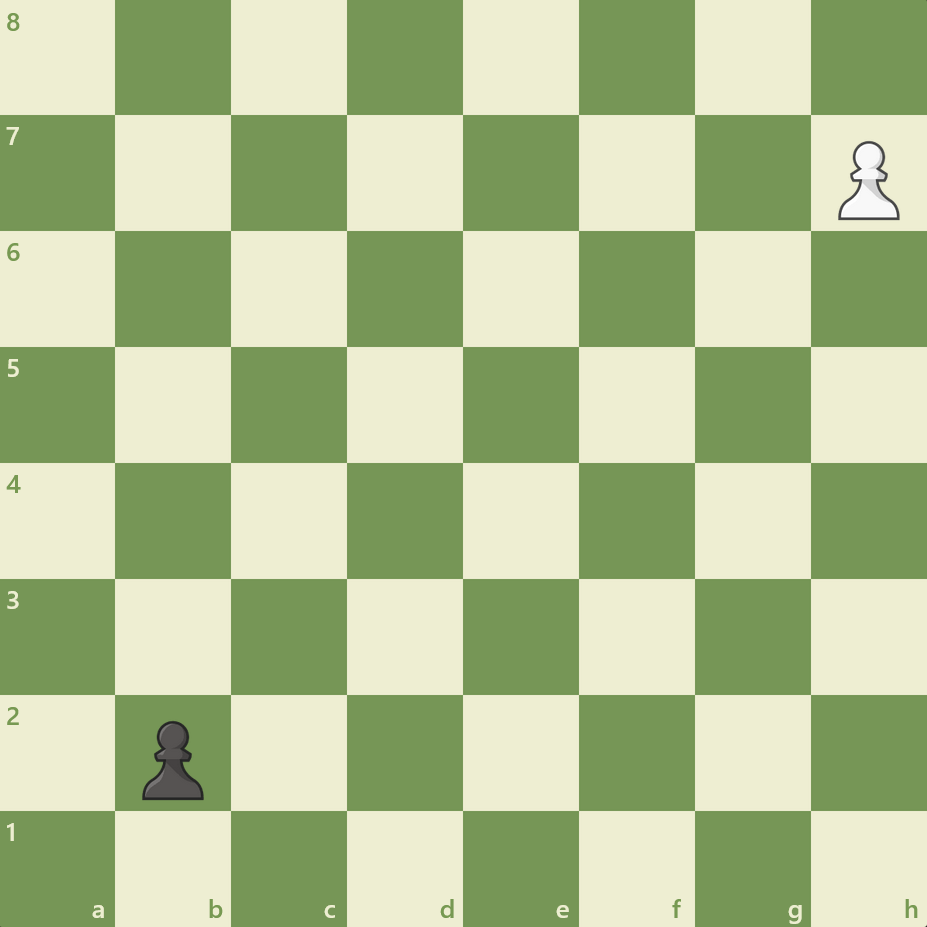

It may seem confusing at first, but it’s not terribly difficult once you’ve had experience with it. Now, let’s look at some bare-bones examples. In the first one, it’s White to move.

In this position, all the pieces are gone, so we can illustrate pawn promotion and pawn promotion only. Since the only move in the position for White is to advance the pawn, he has to move it, and the pawn automatically promotes. Now, if White chooses to promote to a queen, the position will look like this.

1. h8= Q (how to notate promotion).

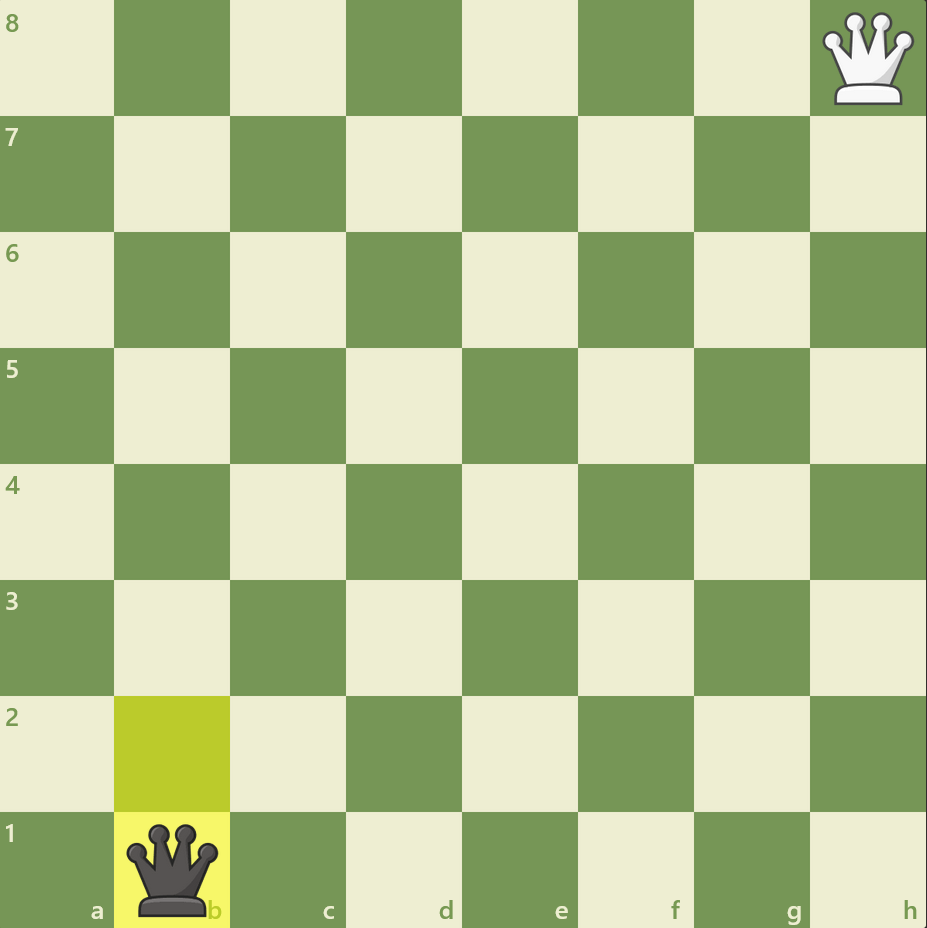

The pawn becomes a queen, signifying promotion. Now, Black wants to follow suit, so he promptly does that.

1… b1= Q

As you can see, the pawn has become a queen as well.

And that is pawn promotion. Just remember that a pawn has to reach the end of the board (8th rank for White, 1st rank for Black) in order to promote, and that you can promote to any piece apart from the King (due to checkmating situations – creating another king is not fair! They’ll have to checkmate you twice…).

Other Theory For Pawn Promotion

Let’s look at some other theory to pawn promotion now.

Here are two additional rules you should memorize:

1) You cannot promote while in check.

2) You can theoretically promote

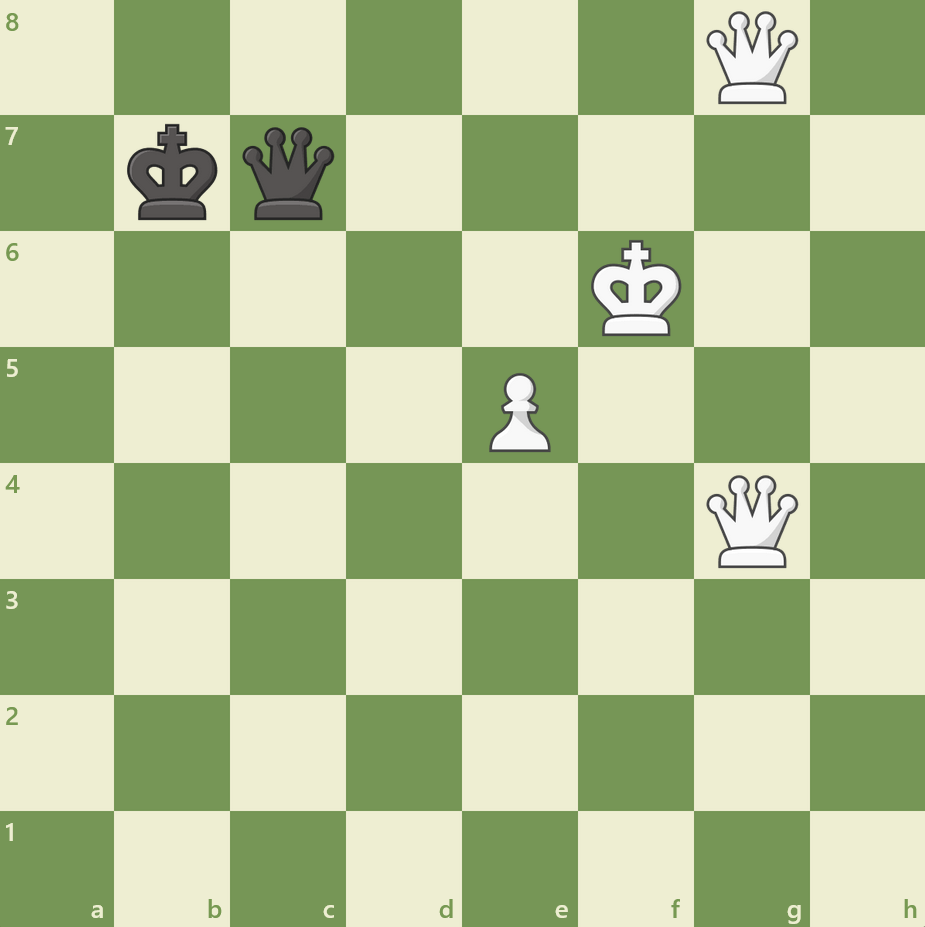

Rule #1 is fairly straightforward: as we know, check overrides everything, and pawn promotion is no exception. In rare circumstances, you can promote your pawn to block check. Let’s see one example, because this is rare (as mentioned). White to move:

On the last move, Black made the mistake of playing 1… Qd8+? Now, White can play 2. h8=Q! Blocking the check and forcing the trade of queens.

That was simple. Now, let’s move on to rule #2.

There are 2 parts of rule #2 that need to be covered. The first is theoretical: there are 9 pawns total that you can promote. So in theory, you can promote all of them to pieces of your choice. (In actual gameplay, this is near impossible, so don’t bother trying).

This rule applies to any game, no matter how many pawns you have on the board ready to promote. If you have 3 pawns ready to promote, in theory, you could promote all of them.

The second part of rule 2 is that you can promote a pawn to pieces you already have. For example, if you have your original queen on the board, you can still promote that pawn to a queen!

And tying back to the first part, you could theoretically promote 9 queens while still having your original queen on the board, having 10 queens!

Sadly, this is not practical and has never happened in a serious game, so let’s forget about that. Just know that you can have multiple of the same pieces on the board thanks to pawn promotion.

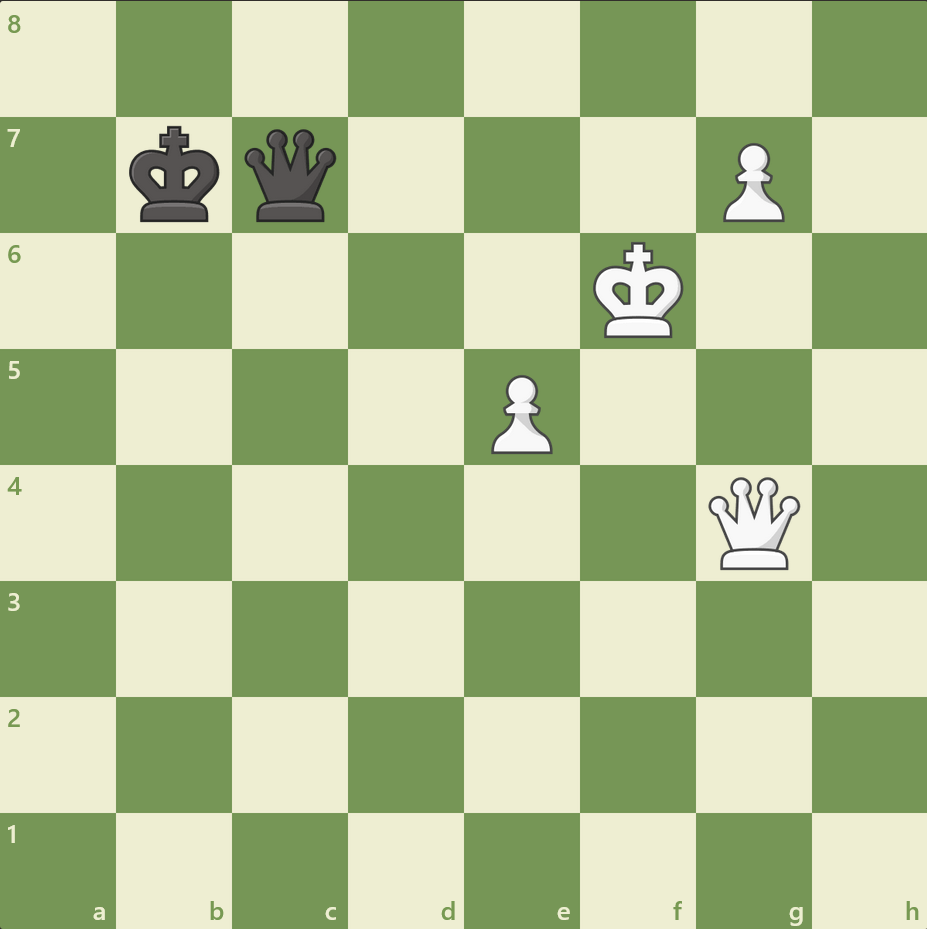

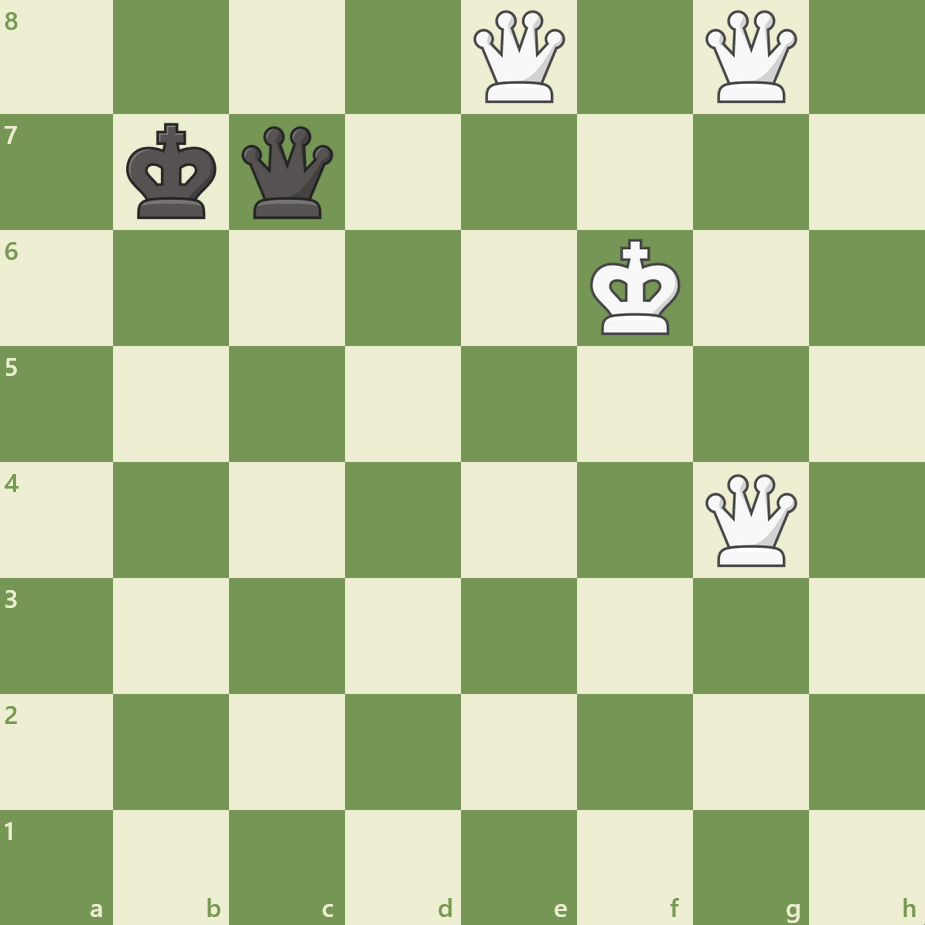

Let’s see an example. It’s White’s move.

Obviously, White is clearly winning this position. He can promote his pawn to another Queen, after which the position looks like this.

As you can see, White has two queens on the board. Let’s say that White’s e pawn miraculously promoted, just to show the definition of overkill.

Now White has 3 queens! Wow.

And that’s about it for pawn promotion. If anything is confusing, go over the examples again, and make sure you understand them. More practical experience is always important: the more instances of pawn promotion in your own games, the better you’ll understand the concept. Now, let’s move onto what I believe to be the hardest concept: En Passant.

En Passant

En Passant is French for “in passing,” which also is the term for a special rule that refers to a specific pawn movement. In line with the definition, this refers to a pawn move that “passes” by another pawn in special circumstances. Wikipedia defines this concept extremely well, so we’ll be using the initial definition, and then breaking it up into more easily digestible chunks.

En Passant:

A special pawn capture that can only occur immediately after a pawn makes a move of two squares from its starting square, and it could have been captured by an enemy pawn had it advanced only one square. The opponent captures the just-moved pawn “as it passes” through the first square. The result is the same as if the pawn had advanced only one square and the enemy pawn had captured it normally. The en passant capture must be made on the very next turn or the right to do so is lost.

Now that’s a lot of information. As I said, we’ll be breaking this up into several chunks, so we can approach this monster one step at a time.

1) What does setting up En Passant look like?

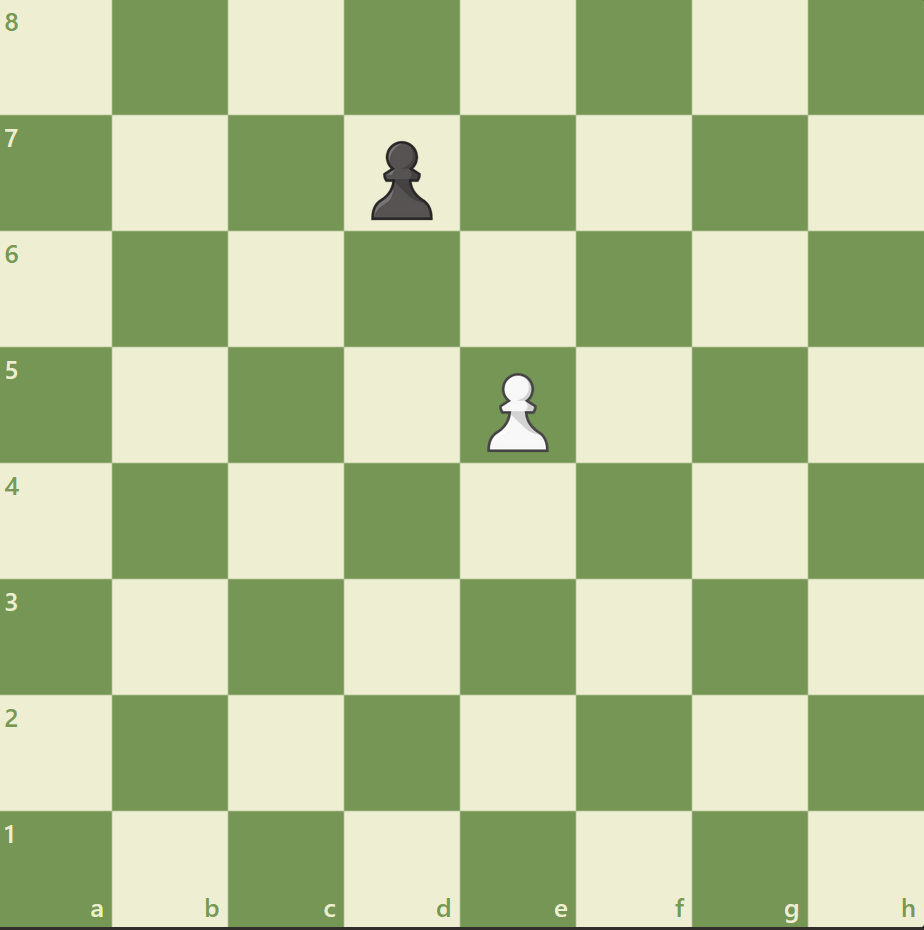

In the definition, this occurs “after a pawn makes a move of 2 squares from its starting square.” Something they forgot to mention is that an enemy pawn has to be next to the pawn after it moves before this capture. So, let’s look at a bare-bones example where a set up En Passant could occur.

In this position, it’s Black’s move. Since his pawn is still on the original square on d7, he can move it 2 spaces to d5, so he does that.

1… d5

2) How does the capture itself work?

With all the following conditions set up, the definition states that “The result is the same as if the pawn had advanced only one square and the enemy pawn had captured it normally.” This part is pretty confusing, so I’ll give a less complex definition.

After all the conditions for en passant are set up, the pawn moves behind the square the enemy pawn was originally on, and captures the enemy pawn.

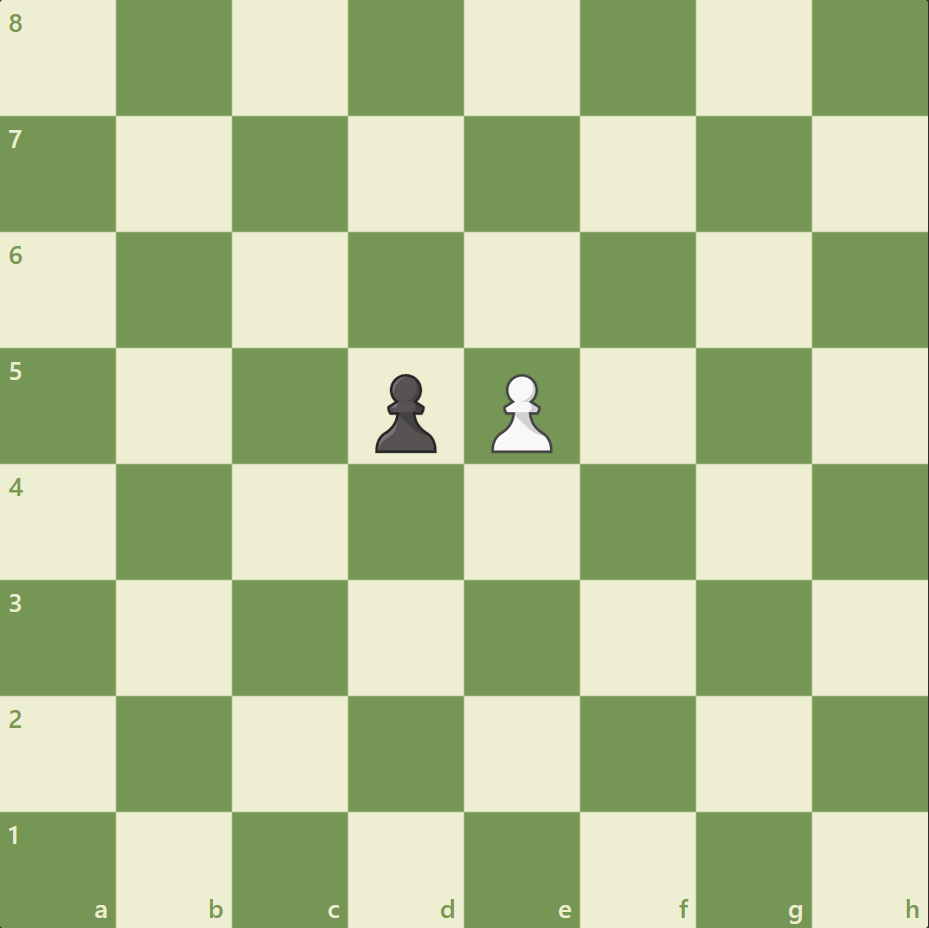

Here’s what it would look like from the original diagram:

It’s the same move order as the previous position, so now White can initiate en passant. The capture looks like this:

As you can see, the white pawn has moved a square behind where the black pawn originally was, and has captured it.

If you’re confused, don’t worry about it. A lot of your early chess improvement is made by just getting familiar with the various concepts in-game, and looking at plenty of examples.

There’s one more tenet of the En passant rule that is very important; that is, “the En passant capture must be made on the very next turn or the right to do so is lost.”

This is pretty self explanatory. Basically, if you don’t take advantage of the en passant conditions right away, you lose your right to play en passant in the exact same way if you did initiate it.

Tip: Just know, as with all chess moves, it’s up to you to decide if the En passant rule by itself is good, but you should be aware that it exists.

By now, you should have a good idea of what makes this move so special, and why this is a rule worth reviewing over and over again until you fully understand how this applies to every day games.

Let’s look at a position from a game now. It’s White’s move, and Black has played d5. As you can see, the pawn has moved 2 spaces from its original starting point, and a White pawn is adjacent to it.

Now, White can initiate En Passant, after which the position looks like this.

As you can see, the pawn has moved “behind” to where the black d-pawn was originally at. In the position, capturing En passant was probably not the best move. After something like 1… Qxd6 2. Nf3 Bg7 3. c3 Nf6, black is doing pretty good.

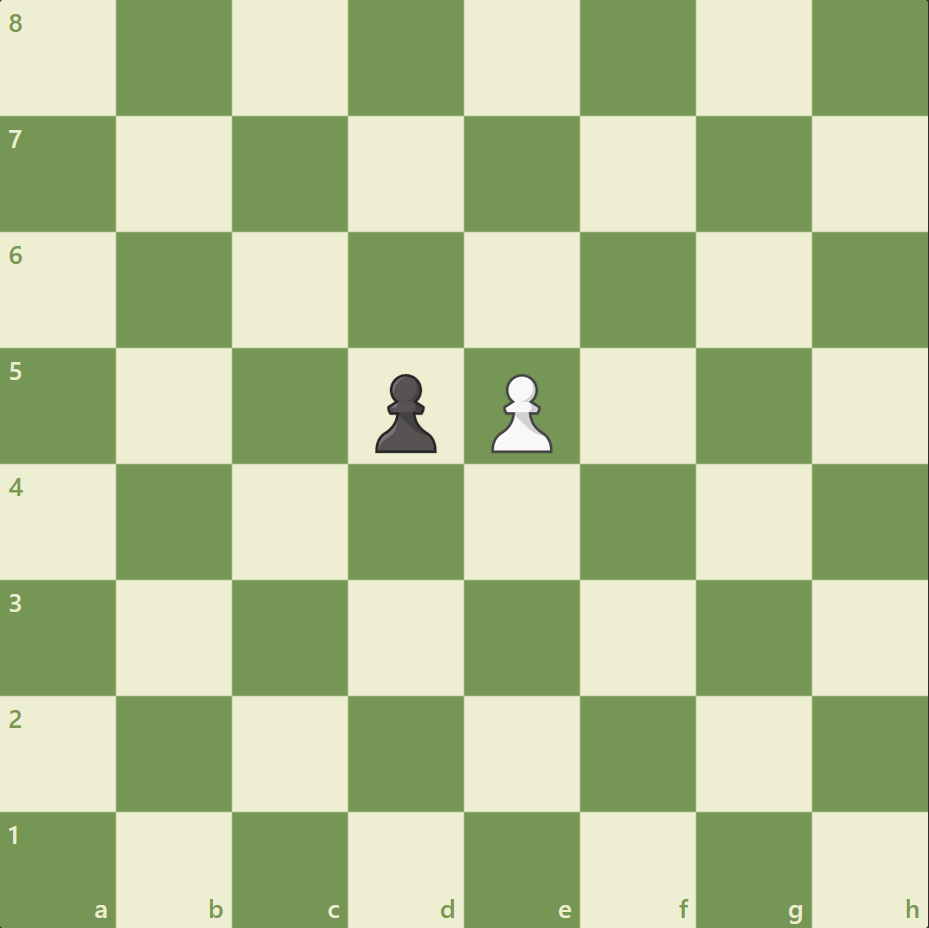

Now, let’s say from the original position, White played (instead of capturing En passant) something like 1. Nf3 Bg7 (good moves from both sides).

The position:

Here, White cannot play En passant because he has forfeited the chance to play En passant.